A research team from Rutgers University-New Brunswick is pushing the boundaries of our understanding of hurricane patterns with an innovative technique that analyzes coastal sediment layers. Through diligent examination of sediments layered beneath New Jersey’s Cheesequake State Park, the researchers uncovered compelling evidence of hurricanes dating back more than 400 years. This groundbreaking study, published in the Journal of Quaternary Science, offers a fresh perspective on how climate change may influence the frequency and intensity of storms.

This method promises to transform the field of coastal sedimentology, moving beyond traditional reliance on tidal gauges and anecdotal historical records. Kristen Joyse, the primary investigator of the study, articulated the challenge researchers have faced: relying solely on instruments installed along coastlines and historical documentation limits our understanding of past storm dynamics, particularly those that predate modern records.

Decoding Geological Narratives: What Sediments Tell Us

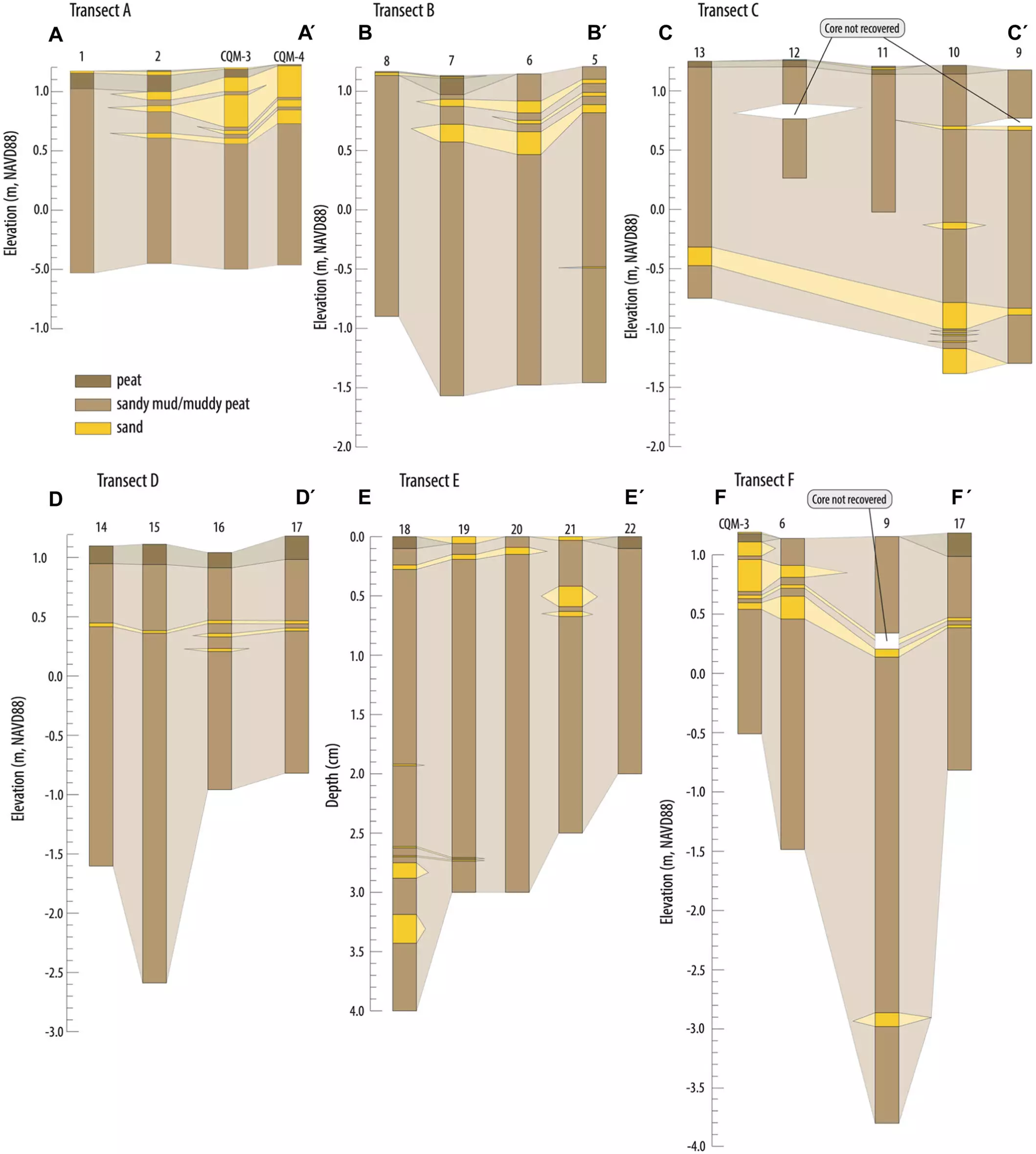

Joyse’s research dives into “overwash deposits,” which occur when hurricane-generated storm surges transport sand from coastal beaches into wetlands. By examining these deposits, the team was able to extend the geological timeline and generate valuable insights into past storm occurrences. The sediment layers analyzed revealed exciting data, including the existence of a hurricane as early as 1584, long before any systematic record-keeping began.

To validate the reliability of these sediment records, the team compared the sediment cores gathered with contemporary tidal gauge data documenting extreme high-water events. This meticulous comparison demonstrated the method’s effectiveness, showcasing eight distinct storm deposits, some of which predate even the oldest gauges still in operation. While tidal gauges offer real-time insights into modern storm activity, they fail to document the rich geological history embedded within the Earth’s sediment.

Combining Modern Science with Historical Inquiry

One of the most fascinating aspects of this study is its intersection of geological research with historical inquiry. Unlike traditional methodologies relying on instrument readings or old newspaper articles, Joyse’s technique allows scientists to reach back in time and extract storm histories that conventional records cannot cover. By extracting sediment cores of up to eight feet deep and analyzing various parameters such as grain size and organic content, the team could distinguish storm-related layers from the underlying sediments.

The sediment reveals a fascinating timeline of hurricanes: from the intense Hurricane of 1938 correlating with deposits dated between 1874 and 1923 to earlier historical storms like the hurricane of 1788. This not only enriches our understanding of storm occurrences in the northeastern United States but also raises intriguing questions about the preservation of certain storms in geological records compared to others.

Lessons from History: Implications for Future Research

The research highlights that although sediment records provide a more profound historical perspective, they are not a comprehensive tool for storm frequency analysis. While the study’s sediment cores identify significant storm events, they fail to capture every extreme weather occurrence, as observed in the discrepancies between tidal gauge data and sediment records.

For example, despite the sediment cores accurately reflecting four major storms, emerging data from the gazes indicates additional extreme water level events that went unrecorded in sediment form. This discrepancy prompts a deeper inquiry: what determines whether a storm’s signature is preserved in sediment, or is lost to time and erosion?

Joyse emphasized that these discoveries pave the way for better hypotheses and further insight into how climate variations could modify storm frequencies in our evolving world.

Charting the Future in Coastal Research

The findings of this research have significant ramifications for predicting future hurricane activity as climate change accelerates. By revealing patterns from the past, scientists can better model potential future storm scenarios. Alongside co-authors, including Robert Kopp, a distinguished professor and director at Rutgers, the team recognizes that while sediment records offer a window into the past, they may not always align with the frequency of storms indicated by present-day instruments.

This research exemplifies the capacity of innovative scientific techniques to reveal hidden histories and suggests that there is much more to learn from the sediment lying beneath our feet. By asking critical questions about storm preservation in geological records, researchers stand at the forefront of a vibrant inquiry that could redefine our tactical approaches to understanding climate dynamics in relation to hurricane activity.

Leave a Reply