In the quest for sustainable alternatives to traditional manufacturing processes, scientists have begun to harness the power of bacteria. These microorganisms are not merely disease-causing entities but can act as remarkable bio-factories, generating essential materials such as cellulose, silk, and various minerals. The excitement surrounding these biological production systems stems from their sustainability—they operate in aqueous environments at room temperature, significantly reducing energy consumption compared to conventional manufacturing. Yet, the application of these biological wonders has historically been limited by a lack of efficiency and output, with the magnitude of their production often falling short of industrial demands.

Creating Living Mini-Factories

To bridge this efficacy gap, researchers, including a team led by Professor André Studart at ETH Zurich, are pioneering innovative techniques to transform bacteria into more potent production systems. The objective is clear: to create engineered bacteria that act as living mini-factories capable of churning out larger quantities of valuable products at a faster rate. This endeavor involves meticulously modifying bacterial genomes or identifying optimal strains for production. By utilizing a natural cellulose producer, Komagataeibacter sucrofermentans, Studart’s team has embarked on an ambitious journey that leverages evolutionary principles to fast-track the generation of bacteria with enhanced production capabilities.

A Novel Approach to Genetic Modification

At the heart of this pioneering research lies a unique methodology advanced by doctoral student Julie Laurent. By employing UV-C light to induce random mutations in the bacterium’s DNA, Laurent effectively created a diverse library of bacterial variants. The creative genius lies in her decision to keep the cells in a dark chamber, thus preventing any DNA repair mechanisms that might typically restore them to their original state. This technique does not merely tinker with genes; it opens up a new frontier in bacterial engineering where random genetic modifications can lead to serendipitous discoveries of high-performing strains.

Following the incubation of the mutated bacteria in droplets of nutrient solutions, fluorescence microscopy allowed for efficient identification of high cellulose-producing strains. Using an advanced sorting system developed in collaboration with ETH chemist Andrew De Mello, the researchers were able to sort through massive batches of bacteria at astonishing speeds. In mere minutes, they analyzed hundreds of thousands of droplets, pinpointing a handful of strains producing 50 to 70 percent more cellulose than the wild type—a tremendously exciting advancement for biotechnology.

Understanding the Genetic Drivers

Digging deeper into the genetic mechanisms behind this improved production, the team discovered that all four high-performing variants shared a common mutation. The key culprit was identified as a protease—a protein degrading enzyme. This finding presents an intriguing twist: the genes responsible for cellulose production remained unchanged. Instead, the protease seems to alter the pathways regulating cellulose synthesis, allowing the bacteria to behave like overzealous producers. This revelation underscores the complexity inherent in biological systems and suggests that modifying regulatory proteins may yield profound effects on material production.

A Game-Changer for Industrial Applications

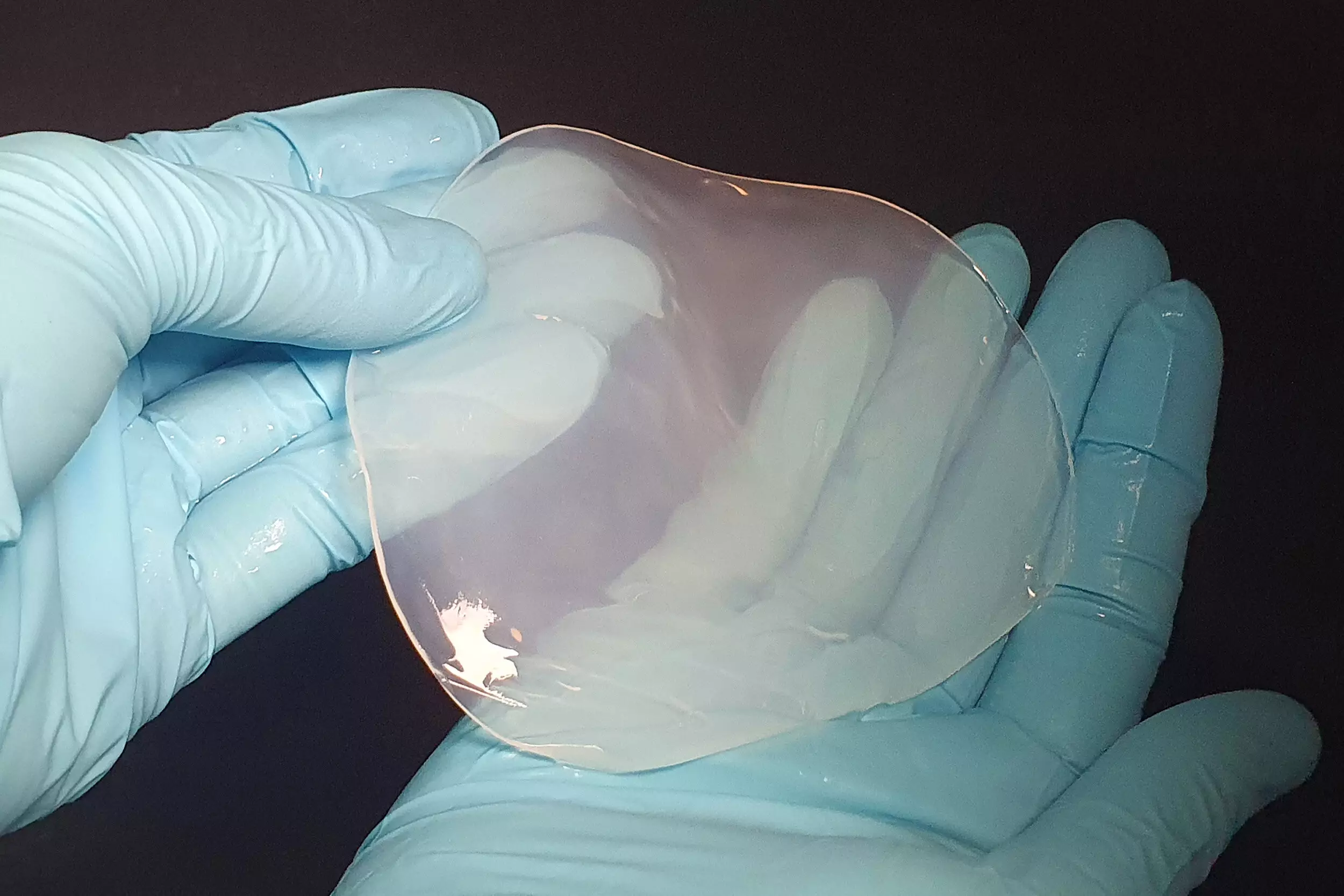

The implications of this research extend far beyond academic intrigue. The cellulose produced by K. sucrofermentans is poised for a range of applications in industries such as biomedicine and textiles, where the demand for high-purity cellulose is escalating. Beyond mitigating bacteria’s infamous reputation, this work illustrates their potential as sustainable production units capable of fulfilling modern demands without the heavy environmental footprint.

As the researchers prepare to patent their innovative approach and the mutated strains of bacteria, they are eager to engage in partnerships with industrial players. The successful implementation of their findings could lead to a significant shift in how cellulose and similar materials are produced, moving from traditional manufacturing to nature-inspired, sustainable methods that can meet the rigorous standards of today’s markets.

Innovating for a Sustainable Future

This groundbreaking research is not just a singular achievement but a testament to the power of innovative thinking in biotechnology. It emphasizes the vast potential of utilizing microorganisms as more than simple components of ecosystems but as collaborators in our manufacturing processes. Professor Studart reflects on this endeavor as not just a milestone for his investigation but a beacon of hope for sustainable material production, sparking curiosity about what other advancements are possible through our understanding of microbial capacities.

The future looks bright for biologically engineered production systems. As researchers continue to unravel the complexities of bacterial engineering, the prospect of creating environmentally sound manufacturing processes grounded in the principles of nature becomes increasingly tangible. This shift has the potential to reshape industries, increase efficiency, and promote sustainable practices—an outcome that is not only desirable but essential for the well-being of our planet.

Leave a Reply