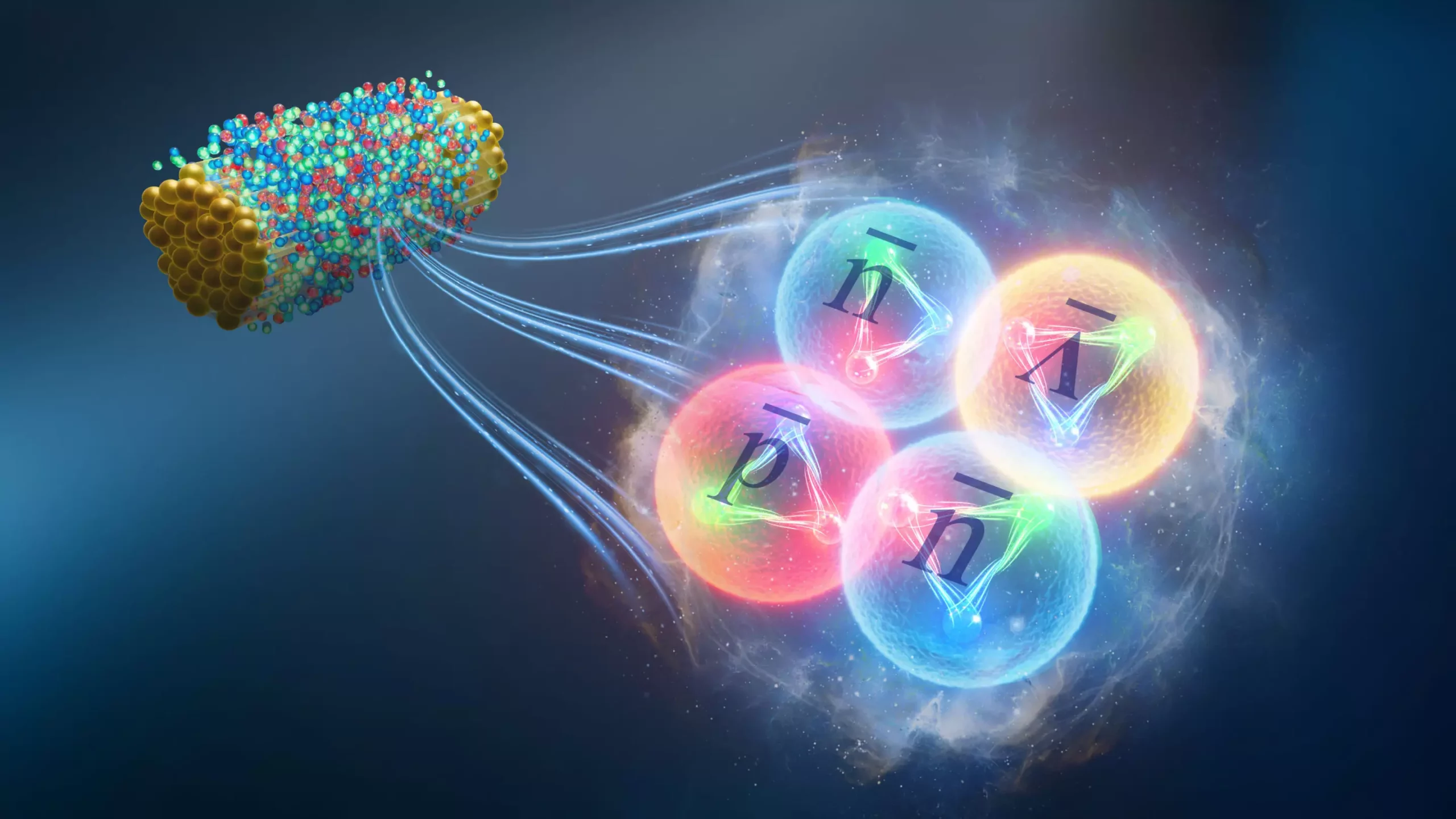

Antimatter, the elusive counterpart to ordinary matter, has long fascinated scientists due to its profound implications for our understanding of the universe. The presence of equal amounts of matter and antimatter during the Big Bang raises the fundamental question: why does our universe predominantly consist of matter today? At the forefront of research into this question is the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) at Brookhaven National Laboratory, where researchers are diving deep into the mysterious properties of antimatter. In an exciting development, scientists from the STAR Collaboration at RHIC have discovered a new type of antimatter nucleus, named antihyperhydrogen-4, that represents the heaviest antimatter nucleus detected so far, comprised of an antiproton, two antineutrons, and one antihyperon.

The detection of antihyperhydrogen-4 emerged through the analysis of particle tracks from atomic nucleus collisions—approximately six billion in total. Utilizing a massive particle detector, STAR Collaborators examined the remnants of these collisions to uncover the less understood regions of particle physics. According to JUNLIN WU, a graduate participant in the experiment, the standard understanding of antimatter is that it shares many properties with matter, including mass and interaction mechanics, making its detectable differences critical for understanding the cosmic imbalance we observe today.

Across vast stretches of time and energy during these high-speed collisions, quarks and gluons emerge from the disintegration of atomic nuclei, forming a “soup” of fundamental particles. This environment closely resembles conditions that prevailed in the early universe, where both matter and antimatter were expected to coexist. However, producing stable antimatter states requires a meticulous configuration of exiting particles, a feat only achieved after combing through massive amounts of collision data.

Antihyperhydrogen-4’s structural complexity is what makes it particularly fascinating. Unlike previous antimatter nuclei, the antihyperhydrogen-4 features an antihyperon, a particle that contains a strange quark—adding a new layer to our understanding of these exotic particles. Prior to this discovery, STAR scientists detected lighter antimatter structures, such as antihypertriton and antihelium-4, setting the stage for this more complex nucleus.

The challenge researchers faced in uncovering antihyperhydrogen-4 was immense. The likelihood of four specific particles—an antiproton, two antineutrons, and an antihyperon—being generated in close proximity during spontaneous collisions is exceedingly rare. Lijuan Ruan, a co-spokesperson for the STAR Collaboration, emphasized the importance of alignment and timing in particle collision events, which mimic the hot, dense conditions immediately following the Big Bang.

To accurately identify the antihyperhydrogen-4 particles, STAR scientists employed sophisticated methods to track particle decay. Each antihypernucleus produces distinct decay products, including the lighter antihelium-4 and pions, which are positively charged particles. Researchers meticulously reconstructed the trajectory of these decay particles—an intricate task given the chaotic nature of collision events, where countless pions are also produced.

The analysis required systematically ruling out random noise amidst a backdrop of numerous events. Emilie Duckworth, a key figure in managing the computational processes, noted that refining their signal detection algorithms was crucial for isolating potential antihyperhydrogen-4 events. Ultimately, the STAR team identified 22 candidate decay events, differentiating the true signals from background noise with considerable precision. Their findings, estimated to confirm approximately 16 antihyperhydrogen-4 nuclei, inspire further research into the inherent properties of antimatter.

The implications of this discovery extend far beyond the laboratory. By comparing the decay rates of antihyperhydrogen-4 to its ordinary matter counterpart, hyperhydrogen-4, scientists look for potential deviations that might hint at the elusive mystery of matter-antimatter asymmetry. So far, no substantial differences were noted, supporting existing theories about the stability and behavior of antimatter.

With these findings, the STAR Collaboration opens pathways to more advanced questions. Understanding the mass differences between matter and antimatter could eventually lead to a deeper comprehension of the fundamental laws governing our universe. As the experiment continues at RHIC, physicists anticipate additional revelations that may bring clarity to the enduring puzzle of why our universe favors matter over its antimatter counterpart.

The discovery of antihyperhydrogen-4 at the RHIC signifies a pivotal moment in particle physics. It exemplifies the intersection of theoretical exploration and experimental research, strengthening our knowledge of the universe’s fundamental components. As science pushes the boundaries of our understanding, each discovery becomes a stepping stone toward answering one of humanity’s most profound questions: why is the observable universe overwhelmingly composed of matter? The STAR Collaboration’s ongoing investigations promise to shed light on this cosmic conundrum, bringing us closer to understanding the fate and composition of everything around us.

Leave a Reply