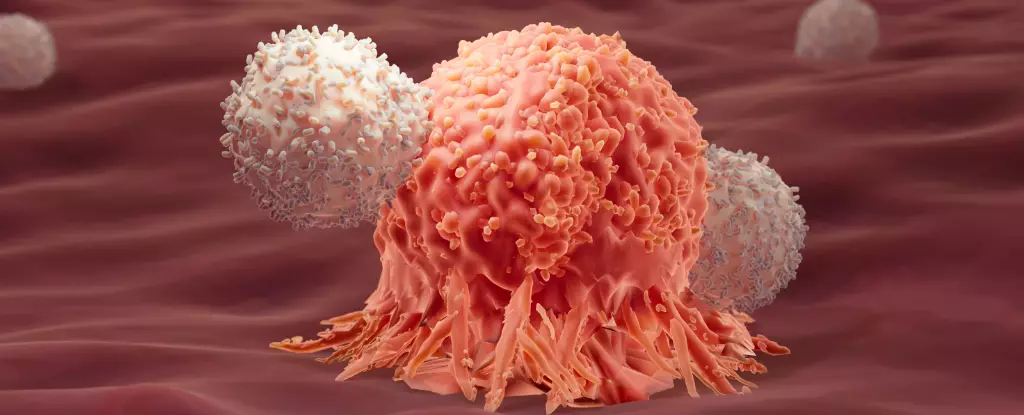

Cancer, a formidable adversary, has long challenged the scientific community to uncover innovative treatments that harness the body’s own defense mechanisms. Recent research illuminates a promising avenue that melds different immune responses, suggesting that the interplay between type 1 and type 2 immunity could enhance the effectiveness of immunotherapy. While the idea of leveraging this “yin and yang” of immunity is still in its early stages, two pivotal studies offer valuable insights into how it may shape the future of cancer treatment.

A Paradigm Shift in Understanding Immune Responses

Traditionally, cancer therapies have focused predominantly on type 1 immune responses, which are geared toward targeting intracellular threats like viruses and tumor cells. This approach has formed the backbone of therapies like CAR-T cell treatment, wherein T cells are extracted from a patient, engineered to better recognize cancer cells, and reinfused. Although this method has shown promise, notably in cases like acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), the reality remains stark: roughly 50% of patients experience relapse within one year of therapy.

In a pioneering investigation by the research team at EPFL, scientists analyzed extensive data from clinical trials to construct a genetic atlas of CAR-T cells from 82 patients. What they discovered was striking—a correlation between long-term remission and markers typically associated with type 2 immune responses, which are usually deemed irrelevant—and potentially even counterproductive—to cancer treatment.

This revelation not only challenges established paradigms but encourages further exploration into how a type 2 immune response could indeed play a role in fighting cancer, despite its historical classification as a less favorable player in immune defense.

The follow-up study utilizing mice provided an experimental ground to test the theory that combining type 1 and type 2 responses could bolster anti-cancer effects. In this experiment, mice suffering from colon adenocarcinoma were treated with either type 1 immunity alone or a synergistic combination of type 1 and type 2 responses. The results were telling: 86% of mice that received the enhanced treatment exhibited complete remission compared to zero success in mice that received the type 1 only treatment.

The implications of these findings are profound. While type 1 immunity is crucial for mounting an initial defense against cancer, the introduction of modified type 2 immune proteins seems to energize T cells, enhancing their longevity and metabolic function. The synergy created by this combination appears to enhance the immune response’s robustness, which holds promise, especially for malignancies that traditionally elude effective treatment.

Dissecting the Mechanisms of Success

An essential aspect of these studies is the elucidation of how switching on the type 2 pathways might bolster the overall efficacy of immunotherapy. The researchers uncovered that the modified immune proteins activated a metabolic pathway known as glycolysis, critical for cellular energy production. This metabolic reprogramming appears to combat T cell fatigue—a common issue where immune cells become exhausted after prolonged exposure to cancer cells, thereby diminishing their effectiveness.

Li Tang, a co-author of the studies, encapsulated the findings aptly, describing the relationship between type 1 and type 2 immune responses as complementary, akin to the concept of yin and yang. This new perspective could redefine the strategic approach to immunotherapy, advocating for a multi-faceted response against cancer that integrates previously neglected elements of the immune system.

While the studies highlight the intriguing potential of this dual-response strategy, it’s imperative to approach these findings with circumspection. The researchers underline that their work establishes correlation—not causation. As the implications unfold, subsequent clinical trials will be necessary to validate these results in human subjects and understand the underlying mechanisms that govern immune functionality in the context of cancer.

If the promise of synergistic immune responses can be realized in clinical settings, it could pave the way for groundbreaking advancements in immunotherapy protocols, potentially improving survival rates and ensuring longer remissions for cancer patients. The traditional boundaries that have compartmentalized immune types may soon dissolve in favor of more integrated approaches, conceiving a drawn line toward enhanced treatment paradigms that could change the lives of countless individuals grappling with cancer.

In an era where personalized medicine is increasingly taking center stage, leveraging the dynamic interplay of immunity as suggested by these studies is a tantalizing prospect—one that beckons further exploration and optimism in the ongoing battle against cancer.

Leave a Reply